An unforgetable trip to Xining, Qinghai Province

I vividly recall one of my early trips to Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province, located at the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. This was likely in the mid-1980s, around 1984 or 1985 (from 1984 until my transfer to Siemens Beijing in 1989, I traveled to China one or two times a year for two to three weeks). The local machinery factory requested our assistance in implementing Siemens automation technology, making this journey quite an unusual experience.

Qinghai Lake – on the way to the Ta’er Monastery

Xining, Qinghai Province in 1984

We first flew from Beijing on an old, shaky Russian jet to Lanzhou, situated on the upper reaches of the Yellow River. Upon arrival, I was supposed to catch a connecting flight immediately. Unfortunately, that flight was canceled, leaving me with no option but to stay at the airport hotel—a dilapidated establishment filled with grime, lacking heating, and frequented by dubious characters. In the middle of the night, an elderly woman brought me hot tea and towels to my room, which could not be locked. The beds were foul-smelling and covered in grime, the toilet was a filthy hole, brown and seemingly never cleaned with any chemicals. My unease grew as I imagined pests lurking in the bed and walls; it was a repulsive and squalid environment. Wrapped in my own clothes and an overcoat for warmth, I had no choice but to lie down, as there was no alternative. The next morning, having skipped breakfast, I continued on to Xining.

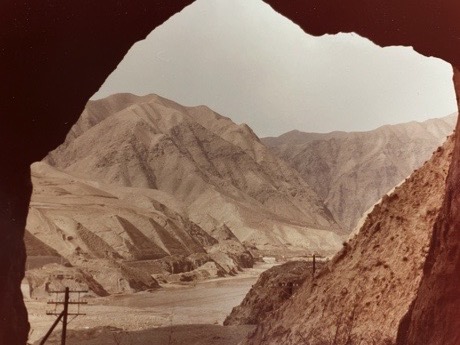

The connecting flight was uneventful at first. However, the view from the plane later revealed a landscape so unique and breathtaking that it still fills me with quiet wonder. From the plane, one could see countless caves prominently positioned in the rugged, treeless mountain slopes.

Journey to Xining – Impressions of the landscape (at the end of the world)

Caves running through the barren, rugged mountain slopes

Gold washers along the rivers of Qinghai Province

Caves, or perhaps even dwellings, carved into the steep mountainsides

Upon landing, I noticed a black limousine waiting directly in front of the docking area. Instinctively, I looked around, wondering if a high-ranking party official had been on the plane with me. To my surprise, the vehicle was there to pick me up. This illustrated the high regard Siemens, as a foreign company, enjoyed in China at that time. Upon arriving in Xining, I inquired about the unusual landscape and was informed that the caves were created by railway workers. They actually appeared more like natural formations still used as small dwellings by locals. Even the locals seemed uncertain about how these caves came to be. At that time, it was safer for the population not to know or be aware of anything not approved by the Party. Even nearly 10 years after the end of the Cultural Revolution, fear of knowing too much persisted. Educated individuals had been persecuted as revisionists during the Maoist era. My friend Karl once recounted meeting a professor working in the fields; this professor preferred to live as a farmer out of fear of his education. What madness! I spent five days in Xining presenting Siemens technology. At the end of my visit, I assisted in automating a small hand-operated machine with the SIMATIC S5 101U, the smallest Siemens controller I had brought for training purposes. Their enthusiasm was so great that I had to overcome my reluctance to accept dinner invitations and sample dishes like sea cucumbers, various snails, and other unfamiliar foods out of politeness. Even the mayor and his entourage attended the farewell dinner. As usual, generous amounts of Mao Tai, a Chinese spirit made from millet and wheat, were poured, and toasts with “Ganbei” — the signal to drink in one gulp — followed one another in quick succession. Participation in these toasts was essential; refusing meant that the entire table would have to forgo alcohol, and the business consequences of such a refusal could be significant. Moreover, these dinners were often the only opportunity for the Chinese to enjoy a full meal and drink. Knowing this, I endured these events, recalling one particular dinner in Beijing when a loyal visitor from headquarters refused to toast with our Chinese hosts. That evening turned into a disaster, and I took the blame for not briefing him on Chinese dining customs beforehand. I later made amends by meeting the hosts alone in my hotel room, opening a bottle, and toasting privately — a small gesture that went a long way in restoring goodwill.

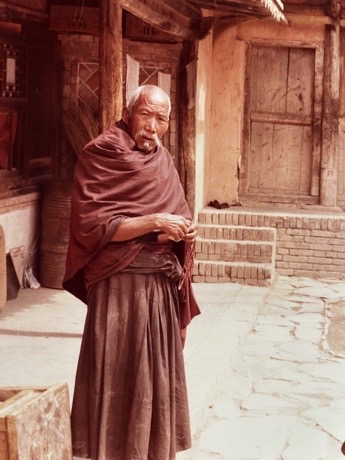

Tibetan visitors and pilgrims at the Ta’er Monastery

Tibetan pilgrims in front of the entrance to the Ta’er Monastery.

A small glimpse of the Ta’er Monastery complex

Monks of the Ta’er Monastery.

Guard in front of the building housing the delicate butter sculptures

I’m not certain, but the figure appears to be Confucius

On the last day of my trip, I made my way to Ta’er Temple, also known as Kumbum Monastery — one of the most important monasteries of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Nestled about 25 km southwest of Xining in Qinghai Province, the monastery rises gracefully on the slopes of Lianhua Mountain, a serene oasis of history and spirituality. Walking through its gates, I was immediately struck by the scale and intricacy of the complex. Founded in 1379 during the Ming Dynasty and expanded in 1577, Ta’er Temple has long been a spiritual hub for Tibetan Buddhists and a home to many high-ranking lamas. The air seemed to hum with centuries of devotion and learning, and it was easy to imagine the monks who had studied, prayed, and meditated here for generations. The architecture itself is breathtaking. The monastery is made up of hundreds of buildings — halls, pagodas, courtyards, living quarters, and study rooms — blending traditional Tibetan and Han-Chinese styles in a way that feels harmonious and timeless. One of the most memorable aspects of Ta’er Temple is its famed “Three Great Arts”: The vibrant murals that cover the walls, telling stories of Buddha and Buddhist teachings in stunning detail.

Meditative prayer wheels at Ta’er Monastery, embodying centuries of spiritual devotion

Butter sculpture, vibrant and full of life and color

The intricate butter sculptures, delicate and ephemeral, yet full of life and color. And the painstaking embroidery and appliqué work, which showcases the devotion and craftsmanship of generations of artisans. Wandering through the halls and courtyards, I felt a profound sense of peace and awe. Ta’er Temple is not just a monument to faith — it is a living testament to culture, art, and spiritual dedication. Visiting it was a truly unforgettable experience.